As I delve deeper into Gaulish Paganism, I find myself increasingly fascinated by the Etruscan civilization. It feels crucial to familiarize oneself with the neighbors of the Gauls in order to gain valuable insights. The Etruscans, renowned for their devout practices, offer a wealth of knowledge that can shed light on our own beliefs. I can’t help but notice striking similarities between the Druides and Uatia of Gaul and the Etruscan diviners along with countless other themes. While conflicts between the Senogalatis and the Etruscans occasionally arose, such as Brennus of the Senones invading parts of Etruria and besieging Clusium, there were also hidden manipulations occurring in the background. Additionally, we joined forces in wars against a shared enemy that of Rome.

Now, I do not identify as a Rasenna pagan (Etruscan pagan), and it would be disrespectful for me to attempt to establish or contribute to Rasenna Paganism. That task is better suited to Rasenna pagans who hold true to those beliefs. Nowadays, it is all too common to witness individuals creating traditions or religious groups based on newly acquired knowledge and presenting them to others. However, traditions, customs, and religions are not mere toys or collectibles that can be constructed or acquired based on reading a book or finding something intriguing. In my opinion, they require extensive time, devotion, and years of understanding.

The purpose of the following information is to deepen our comprehension of the Gauls by exploring the Etruscan culture. It may offer valuable insights that can illuminate the path toward understanding the Senogalatis and the Senodruides.

The Etruscans clearly belong to a distinct realm separate from the Celts, as they were not part of the Indo-European migration and did not speak Indo-European languages. However, for the purpose of research, gaining knowledge about the Etruscans proves highly beneficial.

The Etruscans referred to themselves as Rasenna, although the exact linguistic meaning of this term remains uncertain. Likewise, the origins of the Etruscan people are still a topic of debate, with various theories proposed. One theory, put forth by the Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus, suggests that they are indigenous peoples who have inhabited Etruria, the region occupied by the Etruscans. Etruria was rich in copper and iron, making the Etruscans highly skilled bronzesmiths, a trait that contributed to their prominence in the Mediterranean region.

The Etruscan civilization encompassed the area between the Tiber and Arno rivers, extending south and west of the Apennines, which corresponds to present-day Italy. The Etruscan culture dates back to approximately 1100 BCE, during the Proto-Villanovan culture period, which was a prehistoric civilization. Archaeologists use the term Proto-Villanovan to refer to the early years of the Etruscans, specifically the late Bronze Age period, branching off from the Unfeild culture. This era was characterized by agriculture, hunting, animal husbandry, and the practice of cremation, with ashes placed in pottery urns for burial. Subsequently, five significant periods marked the Etruscan culture: Villanovan, Orientalising, Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic.

The Villanovan period, starting around 900-720 BCE, represents the earliest Iron Age culture in Italy. During the later part of this period, extensive trade with the Hellenic civilization significantly influenced the Etruscans. This contact gave rise to the Orientalizing period (720–580 BC), marked by artistic influences from the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean. The subsequent Archaic period (580–480 BC) witnessed the flourishing of Etruscan culture and expansion of their territories. Magnificent wooden and stone temples were constructed, and large sculptures were created using stone and terra cotta. The Archaic period brought great prosperity to the Etruscans, showcasing their economic and political power.

As the Etruscans reached their peak during the Classical period (480-300 BC), they faced increasing aggression from the Romans. Gradually, the Romans conquered and absorbed Etruscan cities, leading to the decline of Etruscan influence. In the final phase, known as the Hellenistic period (300-50 BC), all major Etruscan cities fell under Roman dominance. It became challenging to distinguish Etruscan art, as many statues were replicas of Greek works, and artistic production declined.

Religion

According to Etruscan belief, their religion was established by two seers named Tages and Vegoia. Tages is revered as a prophetic figure who founded the Etruscan religion, while Vegoia is credited with authoring numerous religious texts. Unfortunately, a collection of texts known as the Etrusca Disciplina, which contained valuable insights into their mythology and divination practices, has been lost to time. However, within this corpus, there was a narrative recounting the story of Tages introducing religion to the Etruscans.

Cicero gives us a little about this myth.

“They tell us that one day as the land was being ploughed in the territory of Tarquinii, and a deeper furrow than usual was made, suddenly Tages sprang out of it and addressed the ploughman. Tages, as it is recorded in the works of the Etrurians (Libri Etruscorum), possessed the visage of a child, but the prudence of a sage. When the ploughman was surprised at seeing him, and in his astonishment made a great outcry, a number of people assembled around him, and before long all the Etrurians came together at the spot. Tages then discoursed in the presence of an immense crowd, who noted his speech and committed it to writing. The information they derived from this Tages was the foundation of the science of the soothsayers (haruspicinae disciplina), and was subsequently improved by the accession of many new facts, all of which confirmed the same principles. We received this record from them. This record is preserved in their sacred books, and from it the augurial discipline is deduced.”

Cicero, Marcus Tullius. “II.50-51”. On Divination.

The Etruscans held a belief system that viewed human life as a small yet significant part of a universe governed by gods. These deities manifested their nature and will in every aspect of the natural world, as well as in the creations crafted by humans. This perspective is evident in the representational arts of the Etruscans, which depicted detailed images of land, sea, and sky, showcasing the integration of humans within their surrounding environment. According to accounts from Roman historians, the Etruscans regarded every bird and berry as a potential source of divine knowledge, and they developed a complex tradition and associated rituals for accessing this information.

Some refer to the Etruscan belief system as immanent polytheism, as it considered all observable phenomena as manifestations of divine power. These deities were believed to constantly interact with the world, their actions capable of being influenced or swayed by mortals. The Etrusca Disciplina, a collection of texts now lost to us, supposedly contained extensive discussions on divination and methods for deciphering the will of the gods. Unlike the Greeks and Romans, the Etruscans seemed less focused on moral and ethical contemplations, instead prioritizing the understanding of divine will and establishing protocols for seeking answers from the gods.

Following the assimilation of the Etruscans, Seneca the Younger remarked in his Naturales Quaestiones II.32.2 that the difference between the Romans and the Etruscans lay in this aspect.

Whereas we (Romans) believe lightning to be released as a result of the collision of clouds, they (Etruscans) believed that the clouds collide so as to release lightning: for as they attribute all to deity, they are led to believe not that things have a meaning insofar as they occur, but rather that they occur because they must have a meaning.

Seneca the Younger, Naturales Quaestiones II.32.2

A Relic of the Cosmos

One of the most revered artifacts is the Liver of Piacenza, a life-sized bronze replica of a sheep’s liver. It bears Etruscan inscriptions throughout and was discovered in 1877 in Gossolengo, a province of Piacenza, dating back to the 2nd century BCE. The Liver of Piacenza served as a tool for haruspicy, the practice of divining the future by examining the entrails of sacrificial animals, particularly sheep livers. It is divided into sections, each containing the names of Etruscan gods and goddesses.

The outer part of this relic consists of 16 sections, as mentioned by Cicero in his work “On Divination” (book 2, 18:42), where he states:

The Etruscans divided the sky into sixteen parts.

Cicero, On Divination 2, 18:42

It seems that this artifact represents a model of the Etruscan cosmos, with each of the 16 sections corresponding to the dwelling place of a specific deity. During divination, an augur would interpret the direction from which lightning struck and associate it with the corresponding dwelling place of the respective god or goddess. Lightning in the east was considered auspicious, while lightning in the west was seen as inauspicious. Other classical writers also refer to the Etruscan practice of dividing the sky.

Pliny, in his “Historia Naturalis” (2.55.143) writes:

They divided the sky into sixteen parts: the first quarter is from the North to the equinoctial sunrise [East], the second to the South, the third to the equinoctial sunset [West], and the fourth occupies the remaining space extending from West to North; these quarters are divided into four parts each, of which they called the eight starting from the East the left-hand regions and the eight opposite ones the right-hand.

Pliny, Historia Naturalis 2.55.143

Servius, in his commentary on Virgil’s “Aeneid” (8.427), states:

From the whole sky,” that is, from every part of the sky; for the natural philosophers say that lightning is thrown from sixteen parts of the sky… Therefore this means: they were making lightning in their own likeness, which Jupiter throws from the whole sky, that is, from the different parts of the sky, meaning sixteen.

Servius, Virgil’s “Aeneid” 8.427

In essence, this relic was employed to interpret and divine the celestial realm. It represents a fascinating area of study, and delving further into its significance could easily become a captivating exploration.

Below is a reconstruction from the work of Alessandro Morandi (1991) Nuovi lineamenti di lingua etrusca, Massari

Outer

- tin/cil/en

- tin[ia]/θvf[vlθas]

- tins/θ neθ[uns]

- uni/mae uni/ea (Juno? Maia?)

- tec/vm (Cel? Tellus?)

- lvsl

- neθ[uns] (Neptunus)

- caθ[a] (Luna?)

- fuflu/ns (Bacchus)

- selva (Silvanus)

- leθns

- tluscv

- celsc

- cvl alp

- vetisl (Veiovis?)

- cilensl

Inner

- tur[an] (Venus)

- leθn

- la/sl (Lares?)

- tins/θvf[vlθas]

- θufl/θas

- tins/neθ

- caθa

- fuf/lus

- θvnθ(?)

- marisl/latr

- leta (Leda)

- neθ

- herc[le] (Hercules)

- mar[is]

- selva

- leθa[m]

- tlusc

- lvsl/velch

- satr/es (Saturnus)

- cilen

- leθam

- meθlvmθ

- mar[is]

- tlusc

Back

- tivs (or tivr “Moon” or “Month”?)

- usils (“of the sun” or “of the day”)

An Almanac of Divining

The Etruscan Brontoscopic Calendar can be found in Johannes Lydus’ “De ostentis 27–38” It is the longest Etruscan text to be found but unfortunately not in its original Etruscan language. The original is lost to us. In the Greek translation of the text Lydus tells us that the calendar was part of the Etruscan disciplina and that Tages provided it to the people.

The term “brontoscopic” derives from the Ancient Greek words “brontos,” meaning “thunder,” and “scopic,” meaning “seeing” or “prediction.” Therefore, “brontoscopic” can be understood as “prediction by thunder.” Comprised of twelve months, the calendar commenced in June and held significance beyond divination, encompassing social, agricultural, religious, and medical knowledge. This calendar was a divination system utilized by Etruscan priests interpreting the celestial phenomenon centered around the observation of thunder and lightning. The belief was that these natural occurrences conveyed messages from the gods, offering glimpses into future events and their implications.

Contained within the calendar are lists of possible omens and events associated with different combinations of thunder and lightning. Etruscan priests, known as haruspices, would consult this calendar to decipher the meanings of specific thunder and lightning patterns, enabling them to make predictions concerning various aspects of life, including agriculture, warfare, politics, and natural calamities. Each distinct combination of thunder and lightning held its own significance, allowing the haruspices to interpret specific events accordingly. For instance, certain patterns might signify a prosperous harvest, while others could foretell the outbreak of war. The Etruscans regarded the understanding and interpretation of these divine messages as a means to comprehend the will of the gods and make informed decisions or take appropriate actions. The Brontoscopic Calendar played a pivotal role in their religious and divinatory practices, empowering them to navigate the uncertainties of the future and seek divine guidance.

Below is a translation of the Almanac/Calendar from the book THE RELIGION OF THE ETRUSCANS Nancy Thomson de Grummond and Erika Simon. Translation by Jean MacIntosh Turfa from the original Greek translation which can be found in Johannes Lydus’ “De ostentis 27–38.

Aisar

For scholarly comprehension, the Etruscan Aisar (gods) can be categorized into four levels: Indigenous deities, Indo-European reflections, Adopted Greek Gods, and Dii involuti or “veiled gods.”

- Indigenous

- Voltumna or Vertumnus – a primordial, chthonic god

- Usil – god(dess) of the sun

- Tivr – god of the moon

- Turan – goddess of love

- Laran – god of war

- Maris – goddess of (child-)birth

- Leinth – goddess of death

- Selvans – god of the woods

- Nethuns – god of the waters

- Thalna – god of trade

- Turms – messenger of the gods

- Fufluns – god of wine

- Hercle – The heroic figure is the offspring of Tin and a mortal woman, nurtured by Uni. He is closely connected with flowing water, holds mastery over animals, and serves as a guardian of herds. In Etruscan art, he is often depicted as a defender against creatures that lie beyond the boundaries of human domains, thus embodying the attributes of a Liminal god. It is important to note that he differs significantly from the Greek Heracles and the Roman Hercules.

- Indo European Reflections

- These gods ruled over the above gods

- Tin – the sky

- Uni – the wife of Tin – She is a goddess of family, women, fertility, and marriage. Mother of Menrva and adopted mother of Hercle. She is part of the Etruscan trinity.

- Cel – the earth goddess – She is the mother of the Giants

- Adopted Greek Gods

- The Greek gods started to make their way into the Etruscan culture around the Orientalizing Period.

- Aritimi (Artemis)

- Menrva (Minerva; Latin equivalent of Athena

- Bacchus; Latin equivalent of Dionysus

- Dii Consentes

- The Dii Consentes are Twelve Etruscan gods that help influence. They may have been connected to astronomical concepts. Arnobius suggests that the Etruscan twelve is broken up into six gods and six goddesses that rise and set together. They acted as councilors to Tin. They had a reputation for being without pity.

- Dii involuti

- The veiled or upper gods are superior to all the other gods; they were never directly worshiped, named, or depicted. We don’t know much about them. Jean-René Jannot suggests that they may represent either an archaic principle of divinity or “the very fate that dominates individualized gods.”

Etruscan Trinity

- Tin

- Uni

- Menrva

Novensiles

There are Nine gods revered by the Etruscan people who possess the power to wield lightning. Each lightning strike was believed to hold divinatory significance depending on its location.

The Disciplina Etrusca provided instructions on how to interpret the various types of lightning. The ancient text also elaborates on Tin’s ability to harness three distinct forms of admonitory lightning originating from different celestial realms. Weinstock delves into the specifics of these lightning types in his book “Libri fulgurales,” page 127. “The first type is mild or ‘perforating’ lightning, which is beneficial and serves to persuade or dissuade. The other two types are harmful: ‘crushing’ lightning, which requires the approval of the Di Consentes, and ‘burning’ lightning, which is utterly destructive and necessitates the approval of the Dii involuti.”

Seneca mentions this in his Naturales quaestiones.

The third manubia Jupiter also sends, but he summons to council the gods whom the Etruscans call the Superior, or Veiled Gods [diis quos superiores et involutos vocant], because the lightning destroys whatever it strikes and everywhere alters the state of private or public affairs that it encounters, for fire allows nothing to remain as it was.

Seneca Naturales quaestiones

Pliny mentions them in his Natural History 2.53.1.

The Tuscan writers hold the view that there are nine gods who send thunderbolts, and that these are of eleven kinds, because Jupiter hurls three varieties. Only two of these deities have been retained by the Romans, who attribute thunderbolts in the daytime to Jupiter and those in the night to Summanus, the latter being naturally rare because the sky at night is colder. Etruria believes that some also burst out of the ground, which it calls ‘low bolts,’ and that these are rendered exceptionally direful and accursed by the season of winter, though all the bolts that they believe of earthly origin are not the ordinary ones and do not come from the stars but from the nearer and more disordered element: a clear proof of this being that all those coming from the upper heaven deliver slanting blows, whereas these which they call earthly strike straight. And those that fall from the nearer elements are supposed to come out of the earth because they leave no traces as a result of their rebound, although that is the principle not of a downward blow but of a slanting one. Those who pursue these enquiries with more subtlety think that these bolts come from the planet Saturn, just as the inflammatory ones come from Mars, as, for instance, when Bolsena, the richest town in Etruria, was entirely burnt up by a thunderbolt. Also the first ones that occur after a man sets up house for himself are called ‘family meteors,’ as foretelling his fortune for the whole of his life. However, people think that private meteors, except those that occur either at a man’s first marriage or on his birthday, do not prophecy beyond ten years, nor public ones beyond the 30th year, except those occurring at the colonization of a town.

Pliny Natural History 2.53.1

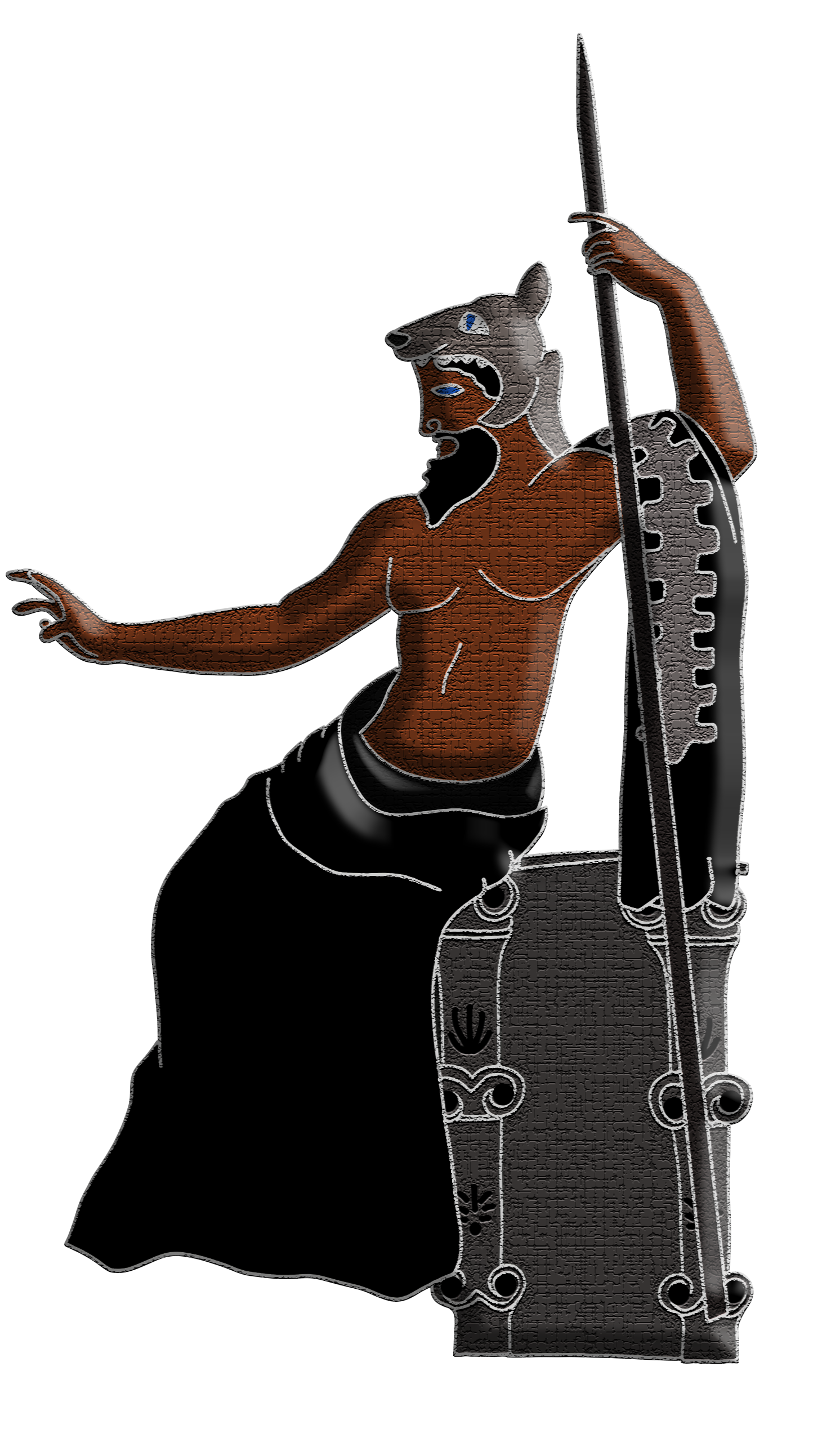

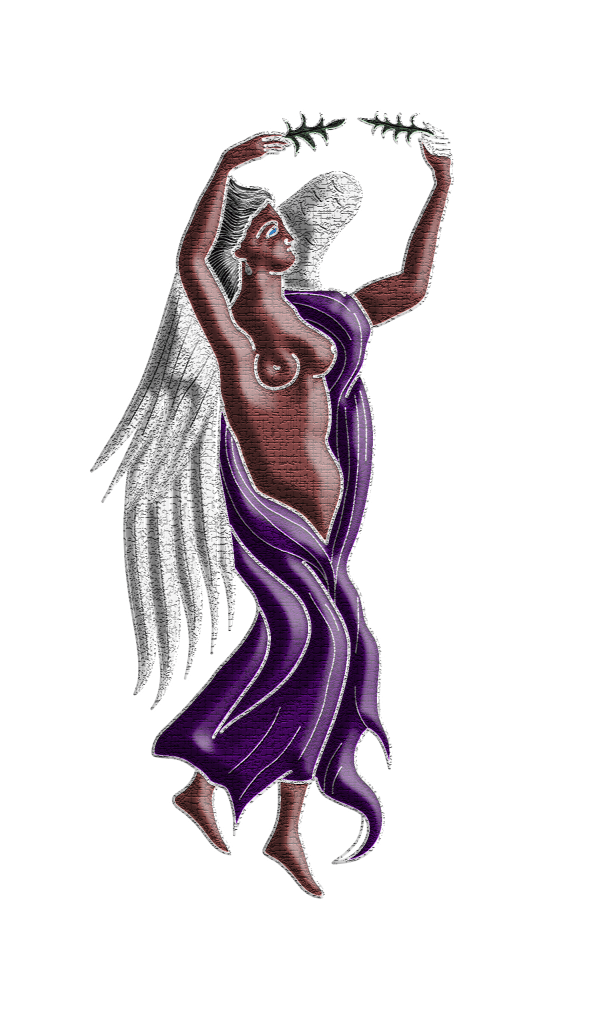

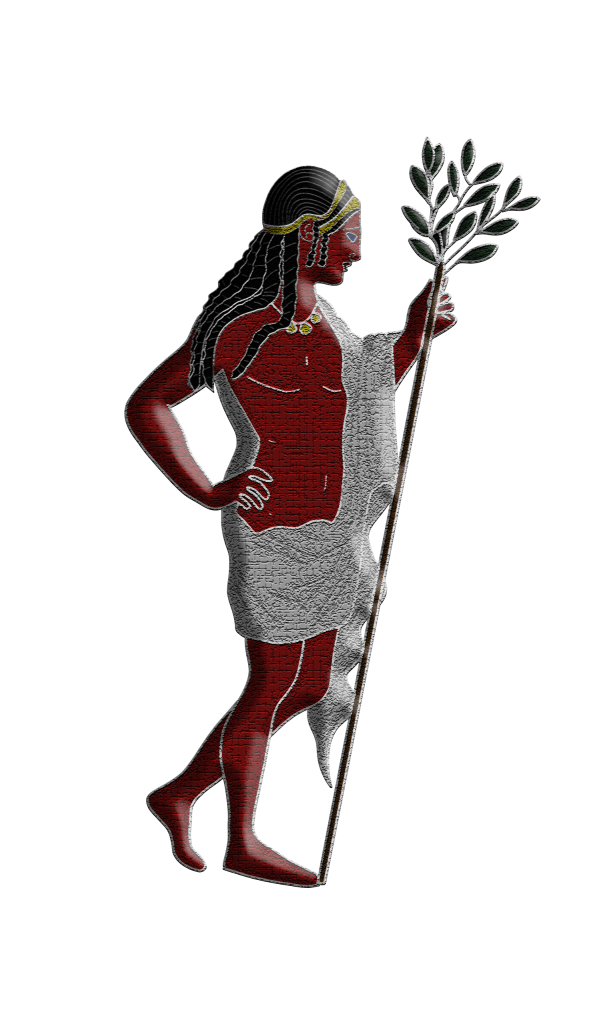

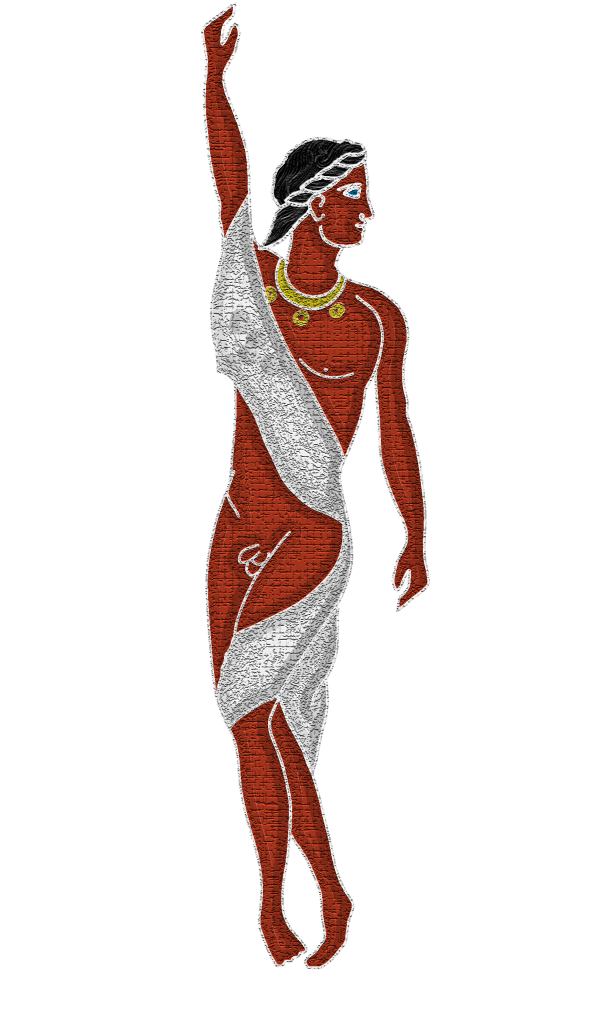

List of the Aisar

I have created a brief summary of some prominent deities, drawing from academic research, comparative mythology, and my own conjecture. Accompanying the text are original artworks inspired by depictions of these gods and goddesses found on ancient relics. I will refrain from portraying a deity if there is no established representation or if there are doubts about its identity. Since I am not an Etruscan pagan, I believe it would be inappropriate to depict a deity without having devoted time to connect with them.

Aita is a deity associated with the Underworld, often portrayed with a beard and a hat made of wolfskin or sometimes with a wolf’s head. Similar to Hades in Greek mythology, he is considered an Underworld god, although there is uncertainty regarding his exact role as the lord of the dead, with speculation being the most common stance. Turms serves as his messenger. Aita’s consort is Persipnei, and both of them are depicted in a tomb wall painting known as the Tomb of Orcus II, dating back to the 2nd century BC. Additionally, Aita can be seen in artistic representations such as a terra-cotta pot from Chiusi (150-100 BC) currently housed in the Berlin National Museum, as well as a relief carving from the 2nd century BC.

Alpan is a goddess associated with fate and having connections to the Underworld is frequently depicted with wings and portrayed in a state of nudity, leading some to associate her with a love goddess. Additionally, she is often depicted holding flowers and leaves, which has led to interpretations of her being a goddess of Springtime. The themes of love and spring are closely intertwined. This goddess serves as a handmaiden to Turan.

Apulu is represented wearing a wolf’s cap, wielding a bow and a lyre, similar to the Greek god Apollo. He has two siblings named Aritimi and Fufluns. Some also associate him with Suri. A life-size terra-cotta figure of Aplu was discovered at the Portonaccio Temple in Veii. Furthermore, there was a sanctuary dedicated to him in Gravisca.

Aritimi is the sister of Aplu and is revered as a goddess of hunting, wielding authority over animals. She shares similarities with Artemis but is believed to be of an older origin. Aritimi is specifically associated with wolves and serves as a protector of human gatherings. It is believed that she holds a significant role in the founding of the town named after her, Aritie.

Athrpa the goddess of fate and destiny is often portrayed with wings and is known to wield a hammer and nails, which she drives into a wall as a symbolic representation of the unchangeable nature of fate.

Atunis (Atune) is a youthful god, believed to be associated with beauty, as evidenced by his frequent appearance on engraved bronze mirrors. Turan, the goddess of love, is often depicted alongside him. He is often compared to Adonis and is particularly revered in the city of Gravisca. It is speculated that he represents an archetypal cycle of life, death, and rebirth, making him a deity connected to vegetation. A festival dedicated to him is held during the summer months to honor his divine presence.

Calu the god of the Underworld is not typically depicted in art. Instead, it is Aita who is portrayed in his place. Given that he is not depicted I opted out from depicting him out of respect.

Catha (Cavtha) scholars engage in a debate regarding whether she is a Solar or Lunar goddess, but regardless, she is referred to as the Daughter of the Sun. She is believed to have associations with childbirth and the Underworld. Catha, as suggested, is depicted alongside two horses responsible for guiding the deceased to the afterlife. There is a connection between Catha and Suri, as they share a cult of worship. Some scholars, like Giovanni Colonna, draw a parallel between Catha and Persephone. In Pyrgi, Catha is depicted alongside Aplu. During the Orientalising period, it is proposed that the elite sought her guidance to ensure the safe passage of spirits to the afterlife and to protect young mothers and infants, thereby securing the hereditary succession of their social class.

Cel, also known as “Cel Ati” or Mother Earth, is revered as the goddess of the earth. Five bronze statues discovered near Lake Trasimeno bear an inscription that reads “mi celś atial celthi I,” which can be translated as “I belong to Cel the mother, here in this sanctuary.” According to mythology, Cel is the mother of the giants known as Celsclan. On a mirror, there is a depiction of a giant accompanied by a goddess whose lower body is adorned with vegetation, leading some to speculate that this goddess is Cel herself. Additionally, the Etruscan calendar includes the month of Celi (September), which is believed to be named after Cel, further emphasizing her importance in their culture.

Charu, similar to the Greek underworld figure Charon, is associated with death in Etruscan mythology. In depictions, he is shown with distinct features, including blue skin, wings, a bird beak, pointed ears, and holding snakes. In the realm of the Underworld, Charu is believed to wield a hammer, symbolizing his role as a guardian of the gates to the otherworld. While Charu is commonly associated with death, there is a debate among scholars regarding his specific role and status. Some propose that he serves as a psychopomp, guiding souls to the afterlife, rather than being the god of the Underworld himself. Additionally, Charu is often depicted alongside Vanth, another type of psychopomp in Etruscan mythology. Notably, De Grummond suggests that Charu may be a type of creature rather than a deity, further adding to the complexity and interpretation of his nature in Etruscan beliefs.

Culsans the dual-faced god, known for his role as a guardian of gateways and doorways, is depicted with two inscriptions and is commonly found portrayed on statues, coins, and sarcophagi. His youthful appearance is consistent across many of these depictions, typically shown wearing boots, a hat, and a torque. The unique aspect of this deity is his two faces, enabling him to observe both forward and backward simultaneously. With four eyes, he serves as a vigilant protector of entrances and exits. His presence signifies his watchful guardianship over these transitional spaces. Though the specific name or identity of this god is not provided, his significance lies in his association with gateways and doorways, emphasizing his role as a guardian.

Culsu serves as both a guardian and guide at the gates of the Underworld. In depictions, she is often portrayed holding a torch, which likely serves to light her path as she navigates in and out of the realm of the dead. Additionally, she is depicted with a key, symbolizing her authority to unlock the gates of the Underworld. Interestingly, some interpretations suggest that the object held in her hand resembles scissors. This symbolism could be associated with the notion of cutting or severing, potentially representing the ending or separation of life. However, it’s important to note that interpretations may vary, and the precise meaning of the object she holds is not definitively established. Overall, this goddess holds significant symbolism as a guardian and guide of the Underworld, responsible for ensuring the transition of souls between the realms of the living and the dead.

Fufluns, also known as Pachies or Pacha, is a prominent Etruscan deity associated with wine, plants, happiness, and growth. He is regarded as the son of Selma and Tinia, two important Etruscan gods. In many aspects, Fufluns bears similarities to the Greek god Dionysus, particularly in his role as a deity of wine and his youthful appearance. Depicted as a beardless youth, Fufluns is often shown alongside apotropaic symbols, which carry protective magical properties. These symbols serve to ward off evil and ensure the prosperity and well-being associated with wine and vegetation. The myths surrounding Fufluns share parallels with the stories of Dionysus, further reinforcing the cultural exchange and influence between the Etruscans and the Greeks. As the Etruscans came under Roman rule, Fufluns was assimilated into the Roman pantheon and merged with Bacchus, the Roman god of wine. This fusion resulted in a transformation of Fufluns’ rituals, influenced by the Dionysian traditions that were already established within Roman culture. Fufluns is a significant deity in Etruscan mythology, representing the vital forces of wine, nature, and joy. Through his association with Dionysus and his integration into Roman religious practices, Fufluns played a crucial role in the cultural exchange and evolution of religious beliefs between the Etruscans and their neighboring civilizations.

Hercle, the son of Uni and Tin, is an Etruscan deity who bears striking similarities to the Greek Heracles. In Etruscan art, particularly on mirrors, Hercle is depicted engaging in various adventures that are not found in Greek or Roman mythology. He is a prominent figure in Etruscan culture, revered as the first mortal to be elevated to godhood due to his exceptional deeds. According to legend, Hercle achieved immortality when Uni, his mother, offered him her breast milk. Hercle is often portrayed as a defender, protecting goddesses against creatures that dwell beyond the boundaries of the human realm. This association has led to the interpretation of Hercle as a god of liminality, bridging the gap between different realms or states of being. Additionally, he is connected to water and is believed to have powers related to its symbolism and significance. As a deity associated with herds and herders, Hercle assumes the role of a protector and a master of animals. Numerous sanctuaries dedicated to Hercle have been discovered throughout the Etruscan lands, as documented by Erika Simons in her book “The Religion of the Etruscans.” While the exact reasons for Hercle’s oracular nature are not explicitly stated, Simons suggests this aspect of his worship based on available evidence. Hercle’s presence in Etruscan religion highlights the cultural exchange and syncretism between the Etruscans, Greeks, and Romans.

Laran is the Etruscan god of war, often portrayed in artistic depictions as a bearded or clean-shaven figure clad in a cuirass and helmet. He is typically shown wielding a lance or spear, representing his martial prowess and role as a warrior deity. Laran’s association with war signifies his importance in Etruscan society and the significance placed on military endeavors. Alongside Laran, his consort is Turan, the goddess of love. This pairing of the god of war and the goddess of love reflects the interconnectedness of these two powerful aspects of human experience. It suggests the belief that love and war are intertwined forces, each influencing the other in profound ways. Laran’s presence in Etruscan art and religious practices highlights the importance of warfare and the role of divine intervention in battles and conflicts. As a god of war, Laran would have been invoked and worshipped by warriors and military leaders, seeking his favor and assistance in their military campaigns. While the specific myths and stories associated with Laran may be less well-documented, his depiction and association with Turan offer insights into the Etruscan understanding of war, love, and their divine manifestations. As with other Etruscan deities, Laran’s attributes and significance may have varied across different regions and periods, reflecting the diverse nature of Etruscan religious beliefs.

Lasa, the goddess of fate in Etruscan mythology, is commonly depicted in artistic representations as a winged and adorned figure, often shown nude and adorned with jewelry. In funerary sculptures, she can be seen holding a scroll and an alabastron, which has sparked speculation regarding her association with death and the afterlife. The presence of the scroll suggests a connection to the recording of an individual’s deeds or life events, possibly indicating a judgment or assessment in the Underworld. The alabastron, a vessel used for holding perfumes, could symbolize the anointing of the deceased or serve as an offering made in their honor. There is mention of the Lasae, a group of goddesses depicted similarly to Lasa. These figures are often interpreted as guardians, overseeing and protecting individuals throughout their lives and continuing to watch over their graves after death. Drawing parallels with Roman culture, where guardian spirits known as Lares were believed to be the ghosts of ancestors tied to the land, there may be linguistic and conceptual connections between Lasa and Lares. Lasa’s association with Turan, the goddess of love, further highlights the interconnectedness of different aspects of life, including fate, love, and death, within Etruscan beliefs. The exact nature of Lasa’s role and significance may vary in different contexts and regions, but her presence in funerary art suggests her involvement in matters of destiny and the afterlife.

Menrva, the goddess of war, art, wisdom, and medicine, is regarded as the child of Uni and Tinia in Etruscan mythology. In Martianus Minneus Felix Capella’s writings, Menrva is mentioned as one of the nine Etruscan lightning-throwing gods, often depicted with a lightning bolt. Influenced by Greek art, later Etruscan representations of Menrva often portray her with a Gorgoneion, which grants her a helmet, spear, and shield. She is also associated with Hercle and is depicted as his protector or companion in various depictions. Numerous temples were dedicated to Menrva, with notable examples being the Portonaccio Temple at Veii and the Pratica di Mare at Lavinium. The discovery of various offerings suggests that she was revered as an educator and held a special place in the hearts of the people. The origin of Menrva’s name remains a subject of debate. Some scholars, such as Tiziano Cinaglia, propose that it has Etruscan roots, possibly derived from the Italic moon goddess *Meneswā, meaning “She who measures.” It is believed that the Etruscans adopted the Old Latin name *Menerwā and transformed it into Menrva. Another perspective, put forth by Carl Becker in his work “Modern Theory of Language Evolution,” suggests a PIE root *men-, which is primarily associated with memory-related words in Greek, such as “mnestis” meaning “memory, remembrance, recollection.” Menrva appears to have had a significant cult following in the Etruscan lands, and her multifaceted domains of war, art, wisdom, and medicine reflect her diverse and revered status in Etruscan society.

Nethuns is associated with water, including wells, seas, and other bodies of water. He is frequently depicted in a similar manner to Poseidon, with a beard and holding a trident, symbolizing his power over the waters. In some depictions, he is shown wearing a ketos headdress, which further emphasizes his connection to the sea. The name “Nethuns” is derived from the Latin “Neptunus,” highlighting the parallel between Nethuns and the Roman god Neptune, who is also associated with water and the sea. Nethuns embodies the forces and mysteries of water.

Nurtia is an Etruscan goddess associated with concepts of time, fate, destiny, and chance. A temple dedicated to her can be found at Volsinii (present-day Orvieto). One notable ritual practiced at her temples involved hammering a nail into the building each year, symbolically fixing the fates for that particular year. This custom of marking the passing of time and the progression of destiny is mentioned by Livy, the Roman historian, in his work “Ab urbe condita.” The presence of nails at the temple of the Etruscan goddess Nurtia, as observed by the diligent researcher Cincius, served as a physical representation of the passage of years. Cicero also references a form of timekeeping where the “nail of the year” is to be moved, suggesting a method of marking time or tracking the progression of events. This practice bears resemblance to certain Roman calendars that employed the movement of a peg or similar mechanism to indicate the passage of time.

Selvans is associated with forests, woodlands, pastures, and sacred boundaries. While only one depiction of Selvans exists, it portrays him as a figure adorned with only boots and a unique headpiece resembling a boar or bears head. Despite the limited visual representation, Selvans appears to have held significant importance in Etruscan religious beliefs, as evidenced by references in inscriptions and the presence of votive offerings dedicated to him. The name Selvans is thought to be connected to the Roman deity Silvanus, who shares similar associations with woodlands and boundaries. This potential linguistic relationship suggests a possible cultural exchange or influence between the Etruscans and Romans in their respective reverence for nature and the guardian of wild places.

Sethlans, an indigenous god of the Etruscans, holds domain over fire, the forge, metalworking, and craftsmanship. Although Sethlans is equivalent to the Greek deity Hephaistos and the Roman god Vulcan, his name does not share a direct etymological connection with them. In Etruscan depictions, Sethlans is often portrayed with his characteristic tools, including a hammer and tongs, reflecting his association with the forge and metalworking. He is also identified by the distinctive cap he wears. Given the Etruscan civilization’s abundance of metal resources, Sethlans likely held great significance in their society. Nancy Thomson, in her book “Etruscan Myth, Sacred History, and Legend,” suggests that the name of the Roman god Vulcanus (Vulcan) has Etruscan origins, citing connections to the Etruscan names Vulca and Vulci, as well as the term velχ- found on the Piacenza liver. This indicates the possibility that Sethlans might have been known by different names among the Etruscans.

Tages, the grandson of Tinia, is a legendary figure according to myth, Tages appeared as a wise child in a field near Tarquinia while an Etruscan was plowing. He imparted profound knowledge of divination, religious rituals, and the establishment of boundaries to the astonished Etruscan. While there is uncertainty regarding specific depictions of Tages in Etruscan art, there are numerous representations of figures associated with him, such as augurs, who are depicted holding a lituus. The lituus is a curved staff used by augurs for divination and interpretation of omens. The teachings and insights attributed to Tages were considered significant and formed part of the Etruscan religious and cultural practices known as the Etrusca Disciplina, which were studied and consulted by Etruscan priests. Tages can be seen as the archetypal embodiment of the augur and haruspex, reflecting the belief in the power of divination and their reliance on interpreting signs and omens to gain insights into the future and make important decisions.

Thanr (also known as Thanur) is associated with midwives and childbirth. She is revered and honored for her role in protecting children during the birthing process. Worship and veneration of Thanr took place in the cities of Caere and Clusium, where her presence was acknowledged and sought during childbirth rituals. One notable association of Thanr is her presence during the birth of Menrva, another significant Etruscan goddess. This highlights Thanr’s role as a guardian and protector of newborns and further emphasizes her connection to childbirth and the well-being of children. Though information about Thanr is limited, her significance in Etruscan society is evident through her association with childbirth and her presence in religious practices focused on ensuring the safe delivery of infants.

Thesan is associated with the dawn, divination, and possibly childbirth. Depictions of her on mirrors often portray her as a winged and naked figure. The etymology of her name suggests connections to illumination, clearness, and divination. As the goddess of dawn, Thesan brings illumination and clarity, both metaphorically and literally. Her role as a dawn goddess is linked to divination, as divination practices shed light on the unknown future, much like the dawn illuminates the darkness of the night. The Etruscan word “thesanthei,” related to her name, means “divining,” “illuminating,” or “brilliant.” As Mary Crane suggests in her The Obscure Goddess Online Directory. Thesan’s association with childbirth stems from her presence at the beginning of the day, symbolizing the beginning of a new life. This connection finds parallels with the beginning of a baby’s life. While she is not exclusively a childbirth goddess, her presence at the dawn and her association with new beginnings contribute to this aspect of her symbolism. In Tuscan folklore, Thesan’s influence continued as a spirit known as Tesana. Tesana would visit mortals in their dreams as the sun rises just before awakening. Her presence in a dream brought words of encouragement, comfort, and good fortune, blessing the individual for the day ahead. This folklore adaptation demonstrates the lasting cultural significance and beliefs surrounding Thesan. Comparisons can be drawn between Thesan and the Greek goddess Eos, who also represents the dawn. The two share similar qualities and functions, further highlighting the connections between Etruscan and Greek mythologies.

Tinas Clenar, the divine twin sons of Tin, are significant figures in Etruscan mythology. They are considered equivalent to the Greek divine twins Kastor and Polydeukes (Castor and Pollux in Roman mythology). In Etruscan art, they are depicted wearing a pointed hat adorned with laurel, as seen in the Tomba del Letto Funebre at Tarquinia. The divine twins hold a prominent role in various mythologies as protectors, heroes, and symbols of duality. They are associated with bravery, prowess in battle, and the protection of sailors and travelers. In Etruscan culture, they likely held similar attributes and were revered as benevolent deities. The pointed hat worn by Tinas Clenar in their depictions is a distinctive feature that represents their divine status. The laurel wreath further emphasizes their association with victory, honor, and divine favor. The imagery of the twins wearing this particular headgear is found in funerary art, suggesting their protective role in guiding and accompanying the deceased in the afterlife. The parallels between Tinas Clenar and the Greek/Roman divine twins highlight the cultural exchanges and influences between ancient civilizations. The Etruscans, like other ancient Mediterranean cultures, often adopted and adapted deities from neighboring civilizations while incorporating their own unique interpretations and symbolism.

Tin, also known as Tinia or Tina, is the chief deity in the Etruscan pantheon and holds a position of great importance. As the god of the sky, he is associated with the overarching celestial realm and is considered the ruler of the divine realm. Tin is commonly depicted with a beard, although there are instances where he is portrayed as beardless. This variability in depictions might reflect different artistic interpretations or regional variations in worship. The presence of a beard often signifies wisdom and maturity, emphasizing Tin’s role as the divine father and leader. One notable aspect of Tin is his association with lightning bolts, which are symbols of his power and authority. The Etruscans believed that Tin possessed three different types of lightning bolts, each serving a distinct purpose: perforating, crushing, and burning. However, according to Etruscan mythology, Tin requires the approval of the Dii involuti, the hidden gods, to wield the last and most destructive bolt. This aspect highlights the complex hierarchy and divine governance within the Etruscan pantheon. The red color of the lightning bolts depicted in Etruscan art is an interesting observation. Color symbolism played a significant role in ancient cultures, and red often symbolized power, energy, and divine potency. The choice to represent Tin’s lightning bolts as red could signify their intense and transformative nature. Tin’s role in protecting boundaries is reflected in the discovery of inscribed stones in Tunisia, marking the presence of Etruscan colonists. These stones serve as physical markers of territorial limits, and their inscriptions indicate the Etruscans’ reverence for Tin and their belief in his ability to safeguard and define sacred spaces. Regarding Tin’s influence on human affairs, the Etruscan religious worldview differed from some other ancient civilizations. While Tin was revered as the highest deity, his interactions with humanity were often mediated through other gods, such as Hercle and Menerva (Minerva), who held more immediate connections with mortals. Tin’s primary focus may have been maintaining cosmic order, harmonizing with other deities, and overseeing the divine realm. Tin reflects the celestial forces, a powerful view of their reverence for the natural elements, and their desire to uphold divine harmony in their cosmology and religious practices.

Tivr, also known as Tiur, is associated with the Moon. However, due to the limited information available and the absence of depictions, there is ongoing debate among scholars regarding Tivr’s gender and specific attributes. The name “Tivr” appears on the back of the Piacenza liver, an Etruscan artifact used for divination purposes. The presence of Tivr’s name on this liver suggests that the Etruscans recognized the deity’s significance and included them in their religious practices, particularly in matters related to divination. While some sources refer to Tivr as a goddess of the Moon, it is important to note that the gender of Etruscan deities can sometimes be ambiguous or fluid. The Etruscans had a pantheon that included both male and female deities, and some deities were not easily categorized into traditional gender roles. Therefore, the possibility exists that Tivr could be either a goddess or a god associated with the Moon. The lack of depictions and limited information about Tivr makes it challenging to determine their specific attributes, roles, or iconography. The study of Etruscan religion and mythology relies heavily on fragmentary evidence and scholarly interpretation. As new discoveries and research emerge, our understanding of Tivr and other Etruscan deities may continue to evolve. Tivr is a deity in the associated with the Moon, but there is ongoing debate among scholars regarding their gender and specific attributes. The name Tivr appears on the Piacenza liver, providing some insight into their significance within Etruscan religious practices, particularly in divination.

Turan is associated with love, peace, fertility, harmony, and vitality. She is often depicted as a youthful girl adorned with wings, wearing robes and jewelry. In some representations, she appears nude, particularly during the Hellenistic period when Greek influences were more pronounced. Turan is known to have a lover named Atunis, and together they have a son named Turnu. The details of their relationship and mythology surrounding them are not well-documented in surviving Etruscan sources, making it difficult to provide a comprehensive account of their stories. Turan’s association with love and fertility aligns her with the Roman goddess Venus and the Greek goddess Aphrodite, both of whom are also associated with love and beauty. The cultural exchanges and interactions between Etruscans, Romans, and Greeks contributed to the assimilation and identification of deities across these different traditions. Turan had an important festival dedicated to her during the month of Traneus, which corresponded to July in the Etruscan calendar. This festival likely involved various rituals and celebrations to honor the goddess and seek her blessings for love, fertility, and harmony.

Turms serves as a mediator between the gods, humans, and the Underworld. He holds a crucial role as a psychopomp, guiding souls to the realm of the dead. Turms is often depicted on sarcophagi alongside other underworld figures such as Charun, the guardian of the Underworld gates, and Cerberus, the three-headed dog. One inscription he is labeled Turmś Aitaś or ‘Turms of Hades In terms of his appearance and attributes, Turms is associated with the Roman god Mercury and the Greek god Hermes. Like them, he is depicted with winged sandals, a caduceus (a herald’s staff entwined by two serpents), and a petasos (a traveler’s hat). These symbols emphasize his role as a messenger and guide between realms. Turms’ name is of Etruscan origin, distinguishing him from other deities in the Etruscan pantheon who have Greek counterparts. This suggests that he was an indigenous Etruscan deity, reflecting the cultural significance and reverence given to him within the Etruscan religious framework. It’s important to note that much of our knowledge about Turms and Etruscan mythology comes from fragmented archaeological evidence and references in ancient texts. Due to the limited surviving sources, there may be variations and gaps in our understanding of Turms and his specific myths and attributes. His depiction alongside other underworld figures and his role as a mediator highlight his significance in beliefs and practices related to the afterlife and communication between different realms.

Turnu is a youthful winged god who is considered the son of Turan, the goddess of love, and holds a significant role similar to the Greek deity Eros. While Eros is known as the god of love and desire in Greek mythology, Turnu shares similar attributes and associations. As a winged god, Turnu is often depicted with wings on his back, symbolizing his swift and ethereal nature. His youthfulness emphasizes the vitality and passion associated with love and desire. Like Eros, Turnu is believed to have the power to inspire romantic love and affection in mortals. Due to the limited surviving Etruscan sources, our knowledge about Turnu and his specific myths and roles is relatively scarce. However, the parallels drawn between Turnu and Eros indicate a similar understanding of the divine concept of love and its influence on human affairs within the Etruscan worldview.

Uni often associated with war, fertility, family, and marriage. She holds a significant position as one of the highest goddesses within the Etruscan pantheon. Uni’s attributes and roles have drawn comparisons to the Greek goddess Hera and the Roman goddess Juno. In depictions, Uni is often portrayed wearing a goatskin cloak, which was a symbol of her association with fertility and motherhood. She is shown carrying a shield, emphasizing her role as a protectress, and a veil, representing her status as a divine and married goddess. The ability to throw lightning bolts, shared by Uni and other Etruscan deities, showcases their power and influence over natural phenomena. The etymology of Uni’s name is a subject of debate among scholars. The suggested link to the Indo-European root “iuni,” meaning “young,” could be related to her associations with fertility and the continuation of life through childbirth. Uni’s importance within the Etruscan pantheon highlights the significance placed on concepts of war, family, and fertility within Etruscan society. As with many deities in ancient mythologies, Uni’s attributes and roles were often intertwined, reflecting the multifaceted nature of divine beings in the cultural and religious beliefs of the Etruscans.

Usil is the god of the sun, holding a prominent role in their mythology and religious beliefs. He is often depicted in Etruscan art, particularly on mirrors and terra-cotta reliefs. One notable depiction of Usil shows him rising from the sea, holding fireballs in each hand. This imagery symbolizes the rising of the sun and its radiating heat and light. Usil is often portrayed with wings, emphasizing his celestial nature and association with the heavens. He is also shown carrying a bow, representing the sun’s rays that bring warmth and life to the Earth. In some depictions, Usil is depicted with a halo or sunbeams radiating from his head, further emphasizing his solar attributes. This imagery draws parallels between Usil and other sun gods, such as the Greek deity Helios and the Roman god Apollo (equated with the Etruscan Aplu). These associations highlight the Etruscan recognition of the importance and power of the sun in the natural world. As the god of the sun, Usil held a significant place in Etruscan religious beliefs and rituals. The sun was seen as a source of light, warmth, and life-giving energy, and Usil was revered as the divine embodiment of these qualities. His imagery and symbolism reflected the Etruscans’ reverence for the sun and its vital role in their daily lives.

Vanth is associated with death and the Underworld. She is often depicted as a female figure, sometimes with wings, and has various attributes and roles depending on the context. In some representations, Vanth is depicted with wings, suggesting her association with the realm of the divine and the ability to traverse between different worlds. She is often portrayed as a psychopomp, a guide who escorts the souls of the deceased to the Underworld. As a psychopomp, she holds a torch to light the way in the dark realms of the afterlife, ensuring that the souls find their proper place. In other depictions, Vanth is shown carrying snakes, which may symbolize her connection to the Underworld and its mysterious and transformative powers. The presence of snakes could also be associated with healing and renewal, as snakes were seen as powerful symbols in Etruscan culture. Vanth’s role as a female demon associated with death reflects the Etruscan belief in the existence of various supernatural entities that governed different aspects of life and the afterlife. As a guardian of the Underworld and a guide for the souls of the deceased, she played a significant role in Etruscan funerary beliefs and practices. Vanth is often described as a demon, the Etruscan concept of demons differed from the negative connotations associated with the term in other cultures. In Etruscan belief, demons were seen as powerful spiritual beings that influenced various aspects of human existence, including the transition to the afterlife. Vanth’s depictions and symbolism highlight her connection to death, the Underworld, and the journey of the soul after death in Etruscan mythology.

Veltha (Veltune/Voltumna) is a deity associated with the Underworld, vegetation, change of seasons and war. Depicted as a malevolent monster, Veltha holds significance as a possible supreme god among the Etruscan pantheon, according to Marcus Terentius Varro’s work “De lingua Latina.”

From them was named Vicus Tuscus’ Tuscan Row,’ and therefore, they say, the statue of Vertumnus stands there because he is the chief god of Etruria.

Marcus Terentius Varro, De lingua Latina book 5 Verses 46

The Fanum Voltumnae, meaning “shrine of Voltumna,” served as a sacred site and spiritual center for the Etruscan civilization as a whole. It was a place where political and religious leaders from different regions of Etruria gathered during springtime to discuss matters pertaining to religion, military affairs, and civic issues. This assembly, often referred to as the Etruscan League of the Twelve Peoples, likely involved prayers and rituals dedicated to their shared gods, including Voltumna, who is believed to have been the state god of Etruria. The parallels drawn between these Etruscan practices and the gatherings of the Druids in Gaul, specifically the Carnutes territory, highlight the significance of communal discussions in religious and political contexts.

We have Livy mentioning the Fanum Voltumnae.

Not only were the Veientines apprehensive of a similar fate, but the Faliscans too had not forgotten the war that they had …. [frequently supported Veii and Fidenae against Rome]. The two states [i.e. Veii and Falerii] sent envoys to the twelve cantons and, at their request, a meeting was proclaimed of the national council of Etruria, to be held at the at the fanum Voltumnae.

Livy, History of Rome’, 4: 23: 4-5

The meeting [at the fanum Voltumnae] passed off more quietly than anybody expected. Information was brought by traders that help had been refused to the Veientines; they were told to prosecute with their own resources a war that they had begun on their own initiative, and not, now that they were in difficulties, to look for allies amongst those whom, in their prosperity, they refused to take into their confidence.

Livy, History of Rome’, 4: 24: 1-2

Projects of war were discussed … in Etruria at the fanum Voltumnae”. There, the question was adjourned for a year and a decree was passed that no [subsequent] council should be held until the year had elapsed, in spite of the protests of the Veientines, who declared that the same fate which had overtaken Fidenae was threatening them.

Livy, History of Rome’, 4: 25: 6-9

Immediately after the start of the siege, a well-attended meeting of the national council of the Etruscans was held at the fanum Voltumnae, but no decision was made as to whether the Veientines should be defended by the armed strength of the whole [Etruscan] nation.

Livy, History of Rome’, 4: 61: 2-3

… the national council of Etruria met at the fanum Voltumnae. The [people of Capena and Falerii] demanded that all the peoples of Etruria should unite in common action to raise the siege of Veii; they were told in reply that … unfortunate circumstances … compelled [the other participants] to refuse. The Gauls, a strange and unknown race, had recently overrun the greatest part of Etruria, and they were not on terms of either assured peace or open war with them. They would, however, do this much for those of their blood and name: … if any of their younger men volunteered for the war they would not prevent their going.

Livy, History of Rome’, 5: 17: 7-10

The precise location of the Fanum Voltumnae remains uncertain, with various archaeologists proposing different sites as potential candidates. Among the suggested locations are Orvieto, Bagnoregio, Tuscania, Viterbo, Montefiascone, Latera, Valentano, Bolsena, San Lorenzo Nuovo, Bisentina Island, Pitigliano, Farnese, and Tarquinia.

Note

There is a wealth of information to explore regarding the Etruscans, and what I have shared so far only scratches the surface. The intention is to shed light on the realm of the Etruscans and make some aspects more accessible, while also providing insights into the customs and worldview of our neighbors of the Senogalatis. This knowledge helps us gain a deeper understanding of ourselves. The information I have provided above serves as a foundation and starting point for further exploration. Remember that we are continuously researching and discovering new elements in this field.

Resources that I used

- The Etruscan World – Jean Maclntosh Turfa

- The Religion Of the Etruscans – Nancy Thomson de Grummond, Erika Simon

- Etruscan Myths – Larissa Bonfante, Judith Swaddling

- The World of the Etruscans – Aido Massa

- Etruscan life and Afterlife – Larissa Bonfante

- Other Resources can be found within the article.

Leave a comment