The Gutuatir, is a role within Gaulish culture that holds great importance. While our knowledge of the specific functions and details of this role from the past may be limited, we can explore its potential significance based on linguistic analysis.

The word Gutuatir is made of gutu-, which means “invocation” and ater meaning ” father. ” The Gutuatir can be interpreted as “the father/master of invocations”, “Master of Voice” or “Master/Father of Inspiration.” This suggests that the Gutuatir held a position related to invoking or calling upon spiritual forces or deities through the power of their voice. The Gutuatir may have been responsible for conducting rituals, leading prayers, or performing invocations. They could have been seen as the authoritative figure who possessed the necessary knowledge, skills, and spiritual connection to effectively communicate with the divine realm through their voice.

As “Master of Voice,” the Gutuatir might have been responsible for training others in the art of chanting, recitation, or ritualistic singing. Their expertise in voice control, intonation, and the use of specific words or sounds could have been seen as essential for invoking the desired spiritual energies or establishing a connection with the divine. The duties and functions of the Gutuatir may have varied among regions and time periods within Gaulish society.

We have a mention of a Gutuatir. The most famous is the Gutuatir from the Carnuticâ (Carnute region or land) which is the place the annual Druid gathering was held. It is also the place we find The Chartres Thuribula, which has a list of inscriptions to summon spirits dating to around the second century CE. Could the summoner have been a Gutuatir? As we know from the inscriptions below that they were still around after the Gallic Wars.

In the mean time, Caesar left Caius Antonius in the country of the Bellovaci, with fifteen cohorts, that the Belgae might have no opportunity of forming new plans in future. He himself visits the other states, demands a great number of hostages, and by his encouraging language allays the apprehensions of all. When he came to the Carnutes, in whose state he has in a former commentary mentioned that the war first broke out; observing, that from a consciousness of their guilt, they seemed to be in the greatest terror: to relieve the state the sooner from its fear, he demanded that Guturvatus, the promoter of that treason, and the instigator of that rebellion, should be delivered up to punishment. And though the latter did not dare to trust his life even to his own countrymen, yet such diligent search was made by them all, that he was soon brought to our camp. Caesar was forced to punish him, by the clamors of the soldiers, contrary to his natural humanity, for they alleged that all the dangers and losses incurred in that war, ought to be imputed to Guturvatus. Accordingly, he was whipped to death, and his head cut off.

Julius Caesar. The Gallic Wars, 8,38

As we can see, The Gutuatir of the Carnutes held a great voice to inspire the people.

Inscriptions

- Autun (CIL 13, 11225 ; AE 1901, 37)

AVG(VSTO) SACR(VM) DEO ANVALLO NORBANEIVS THALLVS GVTVATER V(OTVM) S(OLVIT) L(IBENS) M(ERITO) .

“Dedicated to the august god Anvallus . Norbaneius Thallus , gutuater, fulfilled his vow, willingly, as he should.” - Autun (CIL 13, 11226 ; AE 1901, 38)

AVG(VSTO) SACR(VM) DEO AREA//L//OC(AIVS) SECVND(IVS) VITALIS APPA[R(ITOR)] GVTVATER S(VA) P(2000) . ECVNIA) EX VOTE

“Dedicated to the august god Anvallus . Caius Secundius Vitalis, usher, gutuater, (offered) at his expense, in accordance with his wish.” - Mâcon (CIL 13, 2583 ; 2585)

C(AI) SVLP(ICI) M(ARCI) FIL(II) GALLI OMNIBVS HONORIBVS APVD SVOS FVNC[TI] IIVIR(I) Q(VINQUENNALIS) FLAMINI(S) AVG(VSTI) P[…]OGEN(?) DEI MOLTINI GVTVATRI(?) MART(IS) VI HUNDRED ORDER QVOD IS THE CIV(IS) OPTIMAL AND INNOCENT STATUES PVBL(ICE) TO BE PLACED DECR(EVIT)

“To Caius Sulpicius Gallus, son of Marcus, who performed all honorable offices, quinquennial duumvir, flamen of Augustus , P[…]ogen(?) of the god Moltinus , gutuater of Mars 6 times (?), the order (of decurions) has decreed that statues be erected at the expense of the city, to him who is the best and most virtuous of citizens.” - Le Puy-en-Velay (CIL 13, 1577)

. (VE) I SAW NON(IVM) THE FIERCE FLAME(INEM) IIVIRVM TWICE […

“[…] receiver (?) of the iron mines , gutuater, prefect of the colony, [?], before resting here, I saw my two children become, for one, Nonnius Ferox, flamine, duumvir twice [?].”

The power of voice.

The voice holds immense power and significance in human communication. It serves as a fundamental tool for expressing thoughts, emotions, and intentions, fostering relationships, sharing knowledge, and coordinating actions. Its ability to convey meaning, evoke emotions, and influence others through spoken words is truly remarkable. The voice is intimately intertwined with our individual and cultural identities. It possesses unique qualities, such as pitch, tone, accent, and rhythm, that reflect our personality, background, and experiences. Through our voice, we not only express our individuality but also establish connections with others, shaping our sense of self and asserting our presence in the world.

In various realms, the power of the voice becomes evident. A strong and persuasive voice holds the potential to influence and sway others. Whether it be in public speaking, leadership roles, or everyday interpersonal interactions, the way we use our voice can greatly impact how our message is received. The tone, intonation, and vocal dynamics we employ can convey confidence, authority, empathy, or conviction, making the voice a potent tool for inspiring and motivating others. The voice’s impact extends beyond communication, as it has a profound effect on our emotional state. Different tones, melodies, and rhythms have the ability to evoke a wide range of emotions, from joy and excitement to sadness and tranquility. Music, for instance, beautifully exemplifies the transformative power of the voice, capable of deeply moving us and eliciting strong emotional responses.

The voice plays a central role in numerous religious and spiritual rituals. It is believed to carry spiritual energy, facilitating connections with higher powers and contributing to the creation of sacred atmospheres. Whether through spoken words, chants, or songs, the act of using our voice in rituals enhances participants’ focus, intention, and sense of connection to the divine. The power of the voice lies in its capacity to communicate, express identity, influence others, evoke emotions, and contribute to the sacred. It is a remarkable instrument that shapes our interactions, inspires change, and resonates deeply within ourselves and our communities.

What would a Gutuatir do today?

A Gutuatir is one who invokes or calls upon the gods. The concept of invoking the gods is a common element in many religious and spiritual practices. The Gutuatir are tasked with establishing a connection with the divine realm and calling upon the gods for various purposes, such as seeking their guidance, blessings, or intervention. The role of invokers can take different forms, and their practices may involve rituals, prayers, invocations, or other ceremonial activities. They are priests charged with preaching using their knowledge of the right words and appropriate phrases to invoke, influence, and inspire.

Ritual Performance

Their voice plays a crucial role in the performance of rituals. The vocal elements, including singing, chanting, or speaking in specific tones or rhythms, create a sacred atmosphere, invoke specific energies, and serve as a means of communication between the participants and the spiritual realms.

- Adgarion “to call to” Invocations

The act of invoking holds great importance within our rituals. Coupled with the belief that the voice carries spiritual energy, this helps us to establish a connection of fostering harmonious connections, known as Sumatreiâ, which in turn facilitates the cycle of gifting, called Cantos Roti, between the divine beings, known as Dêuoi, and our revered ancestors, known as Regentiâ. By using a special formula found in different Proto-Indo-European cultures, we can construct invocations using the three components below.- Invocation is the formal communication with the deity or deities, employing descriptive phrases or epithets.

- Argument – encompasses the direct explanation of the purpose behind approaching the deity or deities and presenting reasons that justify the devotee’s worthiness of receiving their blessings.

- Offering signifies the act of expressing goodwill by the devotee through a sacrifice, gift, or offering. This could most likely be the Uatis that makes the sacrifice or offering.

- Natu “Chant, Song, Poem”

The repetitive use of specific words, phrases, or sounds, often accompanied by rhythmic breathing, is common in many spiritual traditions. Chanting and reciting mantras are believed to have a transformative effect on the individual and the surrounding environment. The power lies in the resonance created by the vibrations of the voice, which can help to focus the mind, evoke certain states of consciousness, and connect with the divine.

- Brixtu “incantation, spell; octosyllabic meter”

They would use their voice to recite specific words, spells, or incantations to manifest a desired outcome or influence the spiritual forces as a way to channel one’s intention and direct energy towards a specific purpose.- Brixtu is a form of poetic meter that incorporates octosyllabic lines, alliteration, and a combination of trochaic and dactylic rhythms. It typically consists of any number of lines.

What is the difference between a Gutuatir, Druið, and Bardos?

- Gutuatir: As mentioned earlier, the term “Gutuatir” can be interpreted as “Master of Voice” or “the father/master of invocations.” The Gutuatir was likely associated with the invocation of spiritual forces and deities through their voice. They may have been responsible for conducting rituals, leading prayers, and performing invocations within the Gaulish religious context. Their role could have involved the use of specific words, chants, or sounds to establish a connection with the divine realm and invoke its powers.

- The Druið held a prominent position within the community and is associated with a wide range of roles and responsibilities. They were often seen as the community’s religious leaders, legal authorities, scholars, advisors, and healers. A Druið involved priestly roles as well as those of judicial functions. The primary function of the Druið was to serve as an intermediary between the human realm and the spiritual world. A Druið may have led and officiated in religious ceremonies and rituals. They would have been responsible for ensuring the correct performance of rites, sacrifices, and other religious practices. A Druið was known as the custodians of knowledge and wisdom. They may have served as teachers, passing down religious and philosophical teachings to apprentices and other members of the community. This education likely included myths, sacred traditions, and moral values. A Druið may have provided individuals spiritual guidance, advice, and healing. They could have served as counselors, helping people navigate personal or spiritual challenges and providing remedies for ailments.

- The Bardos is associated with storytelling, poetry, music, and the arts. Bardoi serve as the keepers and transmitters of cultural and historical knowledge through oral traditions. They are skilled in composing and reciting epic tales, songs, and poems that celebrate heroes, gods, and important events. Bardoi often entertain and inspire, using their artistic abilities to convey wisdom, moral teachings, and social commentary. They have a deep connection to the power of language and music and play a significant role in preserving and shaping the cultural identity of their community.

The Gutuatir, Druið, and Bardos are all distinct roles in ancient Gaulish society and Gaulish Paganism today, each with its own functions and areas of expertise. While our knowledge of these roles historically is limited, we draw upon available information to highlight potential differences between them. The Bardos focus was on storytelling of all kinds. The Gutuatir’s focus appears to be on the mastery of voice and the invocation of spiritual forces, whereas the Druide had a broader range of responsibilities, including legal and scholarly functions. It is possible that the Gutuatir could have played a specialized role within the broader Druidic order, focusing on specific vocal practices and invocations. Some Druides may have held the title of Gutuatir.

These roles, Gutuatir, Druið, and Bardos, may overlap in certain aspects, as their functions and expertise are not rigidly confined.

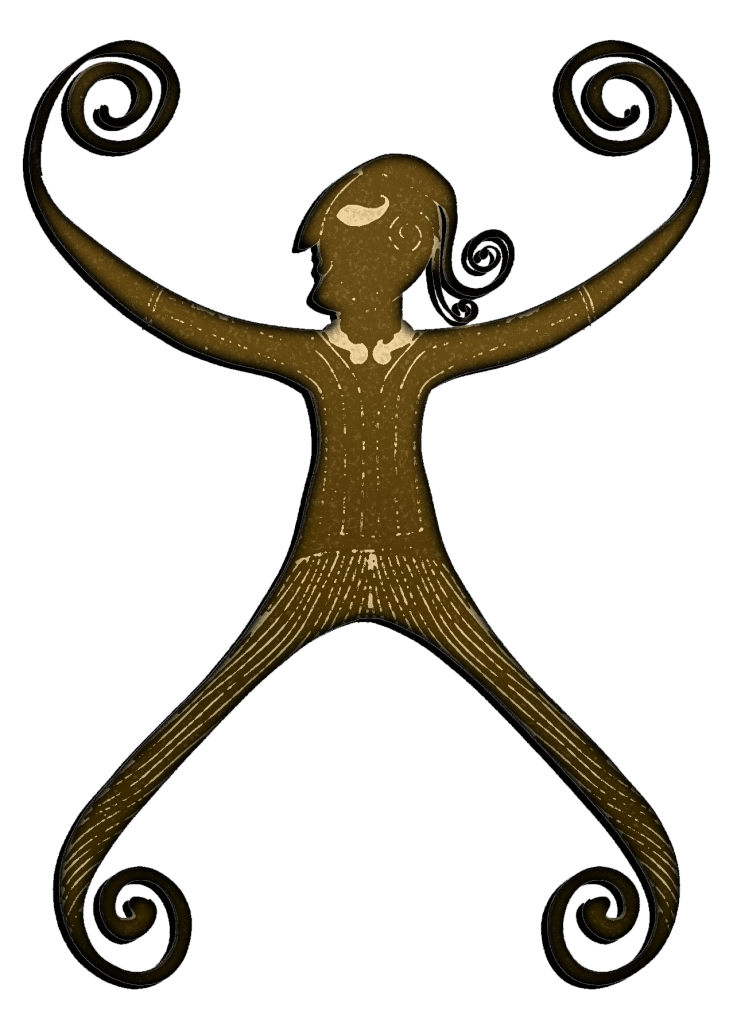

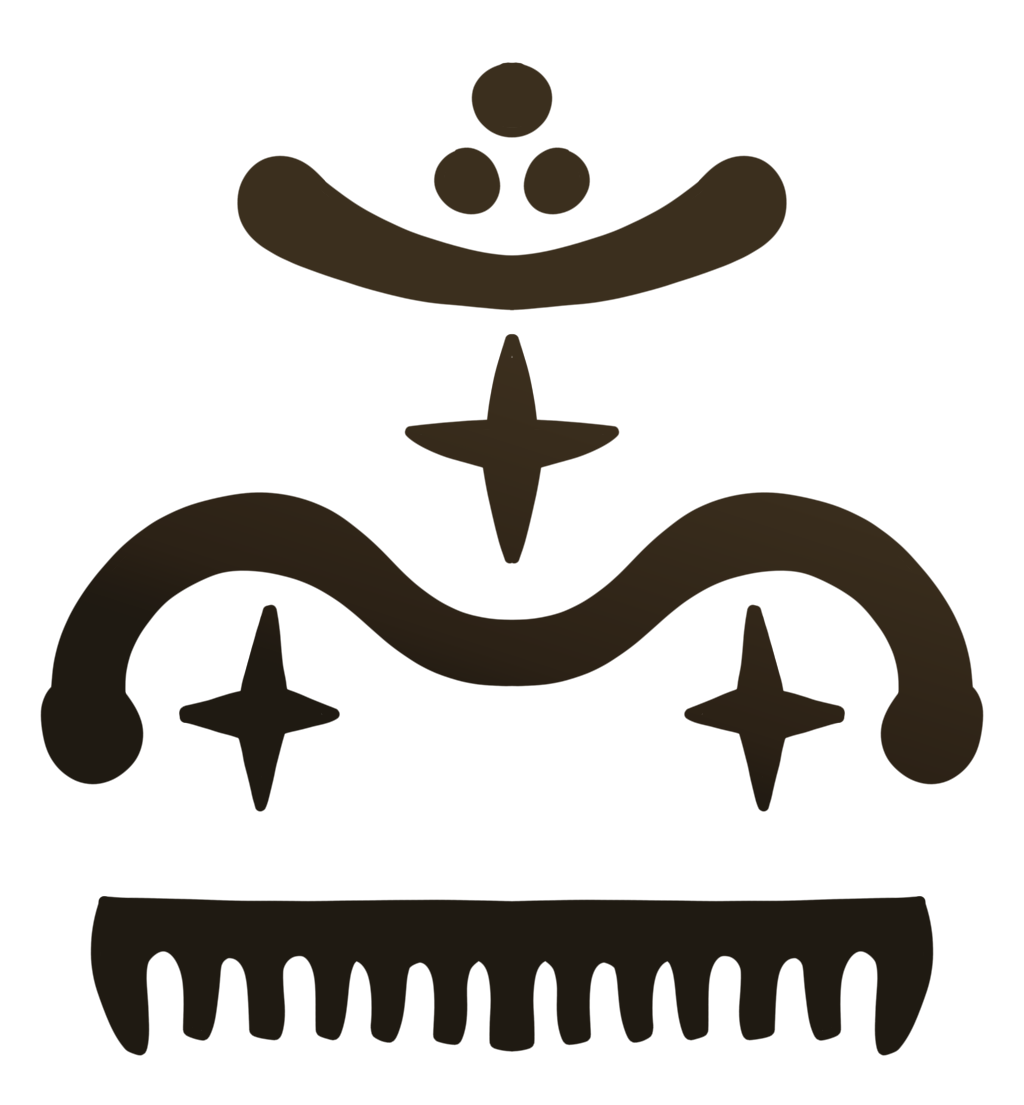

Inscrîbatus (sigil) for the Gutuatir

I used a coin from the Durocasses for the Inscributus of the Gutuatir. The Durocasses area is in modern Dreux in the Eure-et Loir département of north-western France) they are thought to be a vassal tribe of the Carnutes.

We create Inscrîbatus (sigil) to aid in expressing our intentions and materializing our desires. These symbols possess magical energy that becomes activated when observed. By meditating on them, we can deepen our understanding of their significance. They have the power to convert our thoughts into tangible actions and unlock our inner potential. When our minds are clouded and we struggle to comprehend certain aspects, it is crucial to visualize the Inscrîbatus. They serve as a bridge between our unconscious and conscious minds, enabling us to bring hidden aspects to light. These symbols act as seeds of influence, shaping both ourselves and the world around us.

Carnutos

The symbology of the Inscrîbatus for the Gutuatir is rather in-depth, but I will try to translate it.

Three crosslets arranged in a triangle: The three crosslets represent a connection to the divine or spiritual realm. The triangle shape signifies balance, harmony, and the trinity of mind, body, and spirit. It represents the Gutuatir as an invoker between the human and divine worlds. They also symbolize the realms of the past, present, and future, representing the Gutuatir’s connection to ancestral wisdom and the ability to tap into the collective consciousness of their people.

Two curved lines: The curved lines represent the flow of energy or the cyclical nature of life and spirituality. They symbolize the ability of the Gutuatir to navigate and bridge the realms of the sacred and mundane. They also represent the flow of energy, symbolizing the Gutuatir’s ability to channel and direct spiritual forces during invocations. They can also signify the dynamic and transformative nature of the Gutuatir’s work, as they bridge the gap between the spiritual and physical realms.

Three points in a triangle: The three points in a triangle above the symbol further emphasize the trinity and spiritual connection. They represent the divine that the Gutuatir invokes or communicates with. It also signifies the divine triad, representing the interplay of different spiritual forces that the Gutuatir interacts with. Meaning the three realms of Drus.

Ground line consisting of vertical lines: The vertical lines on the ground line symbolize stability, strength, and connection to the earthly realm. They represent the foundation upon which the Gutuatir stands while carrying out their spiritual duties. This also is symbolic to the role of the Gutuatir as a bridge between the divine and the earthly realms. They can also represent the Gutuatir’s grounding and rootedness in their traditions, culture, and the natural world.

The Three levels symbolize the distinct realms of Drus, namely Dubnos (underworld), Bitus (Middle World), and Albios (Upperworld). Additionally, they signify the three pathways within the cycle of gifting involving the Litauinadoi (Spirits of the land), Dēuoi, and the Regentioi (Ancestors). A Gutuatir should be greatly devoted to Sumatreiâ (harmonious connections) that give way to Cantos Roti (Gifting Cycle).

Note

The Druids, Celtic Priests of Nature – Jean Markale

The Druids – Nora K. Chadwick

Rethinking the Ancient Druids – Miranda Green

Leave a comment